In a bold move to reshape Nigeria’s agricultural future, President Bola Tinubu on 23rd June 2025 commissioned 2,000 tractors under the Renewed Hope Agricultural Mechanisation Programme to boost Nigeria’s agribusiness sector and ensure food security, signalling a decisive step toward mechanising the nation’s agricultural system. According to the State House, the intervention aims to bridge the mechanisation gap, enhance food production, and reduce post-harvest losses while promoting youth employment through the agribusiness value chain.

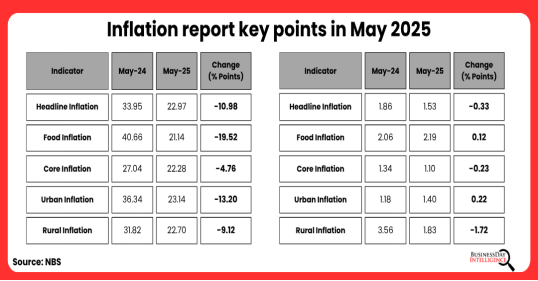

Coming at a time when food inflation hovers above 30 percent and rural productivity remains dismal, the gesture carries symbolic and practical weight. These tractors, if well-distributed and supported with farmer training, maintenance hubs, and affordable access models, could revolutionise food production, increase yields, and empower youth-led agribusiness. Yet, the key question persists: Is this another headline initiative or a genuine lever for change?

“Without institutional reforms and inclusive access models, the Renewed Hope mechanisation push risks repeating these systemic failures.”

Read also: Two years of President Tinubu: Has agribusiness moved forward or merely shifted gears?

Nigeria’s agribusiness realities

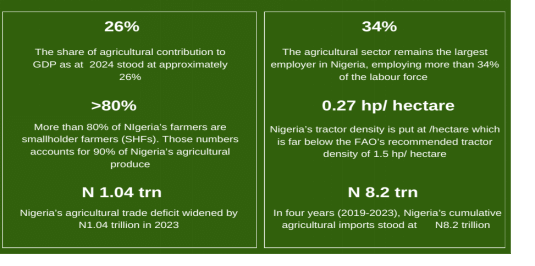

Nigeria’s agriculture sector employs over 70 percent of the population and about 34 percent of the nation’s labour force. Still, it contributes less than 26 percent to GDP, largely due to manual labour, poor access to mechanisation, and fragmented value chains. The sector suffers from one of the lowest mechanisation rates in sub-Saharan Africa. The country has less than 0.3 horsepower (hp) per hectare, a stark contrast to the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO) recommendation of 1.5 hp/hectare for sustainable agricultural productivity.

For a population of over 210 million, Nigeria has between 7,000 and 12,000 functional tractors, according to the vice president of Nigeria, which falls significantly short of the required 2.4 million needed to meet the food production target over the next decade.

With the latest initiative under the Belarus project implemented together with AfTrade DMCC, to deliver the 2000 high-quality tractors, 190 combine harvesters, 12 mobile workshops, 9000 implements, and 9000 spare part kits shows the administration’s commitment to transforming Nigeria’s agriculture sector through modernisation of farming practices and entrenchment of national food security. The initiative is expected to cultivate over 550,000 hectares of farmland, produce more than 2 million metric tonnes of staple food, create over 16,000 jobs, and directly benefit over 550,000 farming households. Other programme components include mandatory operator training, GPS-enabled tracking for accountability, a structured repayment model, and pro bono equipment allocations to research and training institutions.

With improved access to tractors and inputs, this move seeks to unlock agricultural value chains, boost food security, and reduce the country’s growing food import bill, currently estimated at over $2.5 billion annually.

Read also: From cocoa to currency: Unlocking Nigeria’s economic stability through Agribusiness

Food insecurity and food inflation scourge in Nigeria

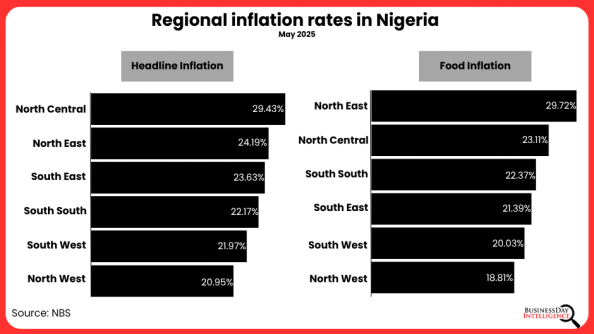

But beneath the vast expanse of Nigeria’s 70.8 million hectares of farmland—a tapestry of maize, cassava, and rice fields—lies a troubling paradox. While agriculture remains the nation’s economic heartbeat, over 100 million Nigerians now face food insecurity, their plates emptying as inflation devours their purchasing power. The numbers tell a harrowing story: headline inflation in the North Central region has surged to 29.43 percent, while food inflation in the Northeast spirals at 29.72 percent, painting a grim picture of deprivation in these areas.

This crisis is not merely economic—it is human. Behind the statistics are 18.6 million people enduring acute hunger, their bodies weakened by empty stomachs, while 43.7 million more resort to desperate measures just to secure a meal. The roots of this calamity run deep, tangled in poverty, inefficiency, and a food system struggling to nourish its own people. This paradox stems from systemic challenges, including poverty (133 million Nigerians in extreme deprivation) and soaring food inflation, which reached 21.14 percent in May 2025, exacerbating hunger.

The government, recognising the urgency of tackling food insecurity, and the Minister of Agriculture and Food Security, Abubakar Kyari, recalled President Tinubu’s July 2023 declaration of a state of emergency on food security, which placed mechanisation at the heart of the Renewed Hope Agenda. In response, four key mechanisation-driven initiatives were introduced: the John Deere Tractorisation Programme, the Greener Hope Project, the Green Imperative Programme, and most recently, the Belarus Tractor Scheme.

Over 2.33 billion people globally face the threat of food insecurity, making it a formidable global concern. Food insecurity remains a pressing challenge in Africa, with Nigeria ranking highest in the region. While studies confirm that food insecurity exists across all regions of Nigeria, its prevalence is disproportionate. The Northeast experiences the most severe food insecurity, followed by the North Central.

Nigeria’s struggle mirrors a global plight, and so in Africa’s most populous nation, the stakes are uniquely high. Without systemic reform, the fields may remain fertile, but the people will starve. The time for half-measures has passed; only decisive action can turn the tide.

Read also: Five funding opportunities for agribusinesses in 2025

Concluding thought

Nigeria’s mechanisation deficit remains a critical bottleneck to agricultural productivity. With fewer than 15,000 functional tractors servicing over 70.8 million hectares of arable land, the country’s tractor density stands at less than 0.3 hp/hectare, far below the global benchmark. This translates to an alarming mismatch—one tractor per 2,700 farmers, compared to one per 300–400 in countries like India or Brazil.

Previous mechanisation initiatives have faltered due to poor maintenance culture, lack of skilled operators, and limited access to affordable finance for smallholder farmers. The absence of rural infrastructure—bad roads, weak electricity, and inadequate storage—further hampers the efficient use of machinery.

Furthermore, previous initiatives have been marred by the scourge of elite capture, where tractors end up with political actors or commercial farmers in urban fringes, excluding the rural poor. For example, in some states, tractors meant for cooperatives ended up idle or resold due to unclear ownership and mismanagement. Without institutional reforms and inclusive access models, the Renewed Hope mechanisation push risks repeating these systemic failures.

More than machines, the tractors must become symbols of a larger structural shift—one that prioritises rural infrastructure, land reforms, access to credit, and private-sector partnerships. If sustained and strategically implemented, this initiative could mark a turning point for inclusive growth, food security, and Nigeria’s long-elusive agro-industrial revolution. But without an ecosystemic approach, 2,000 tractors may plough the surface of deeper problems.

Join BusinessDay whatsapp Channel, to stay up to date

Open In Whatsapp